Smoke on the water - Hungarian Wine House tasting

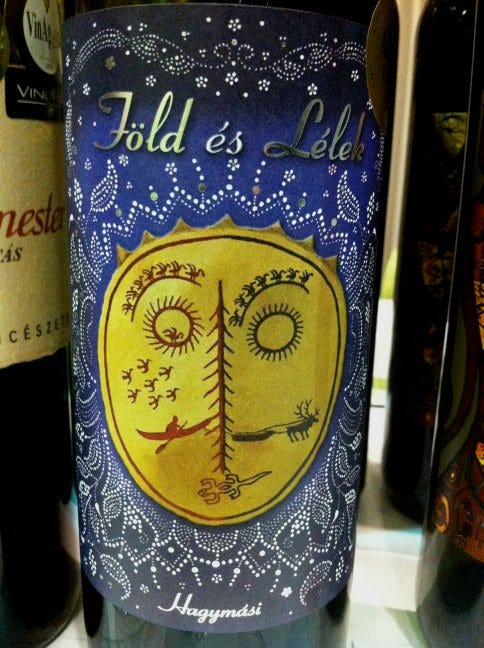

Colourful labels on the Hagymási Pincészet stand

Any bon-viveur worth their salt will be familiar with Hungary's most famous vinuous export - Tokaji Aszu. This luscious yet refreshing nectar has assured Hungary's place on the international wine map for the last 400 years. Additionally, those of a certain age may remember when Eger Bikavér (AKA "Bull's B…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Morning Claret to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.