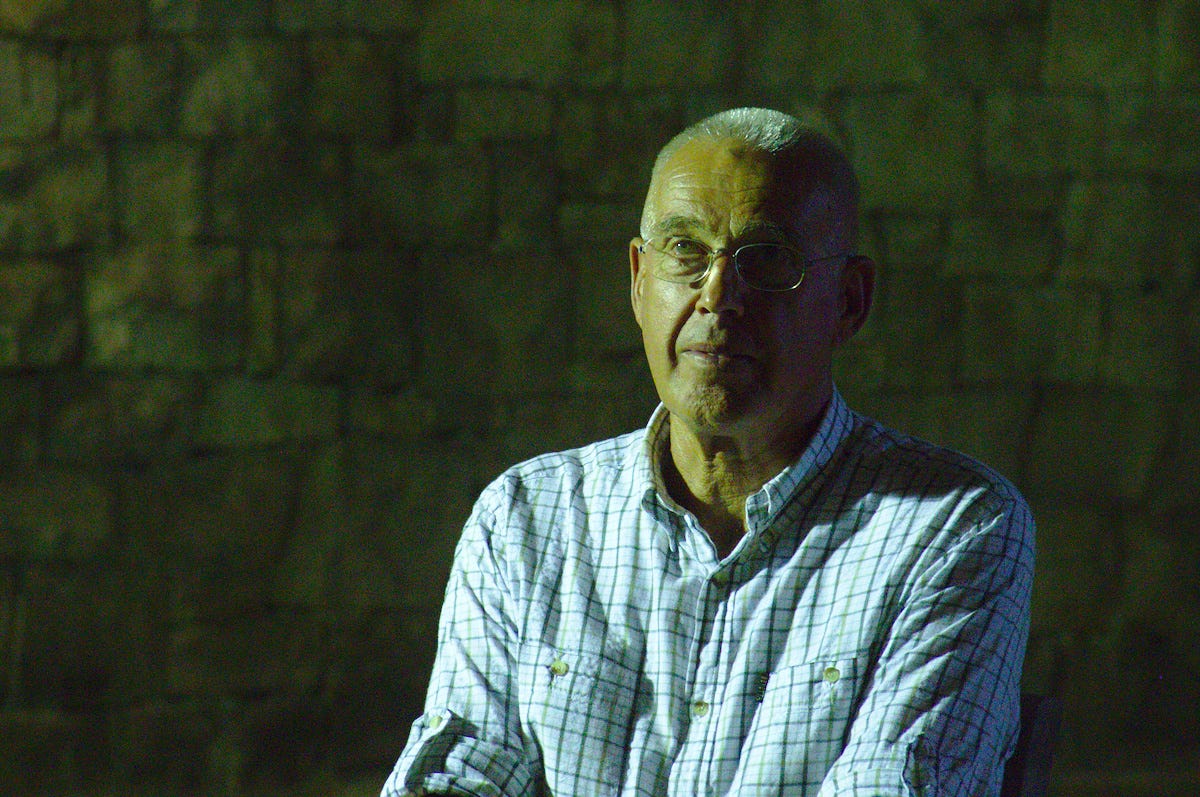

Worth the wait - Gravner's Ribolla Riserva 2003

Almost every week, Simon selects an orange wine (a white wine made with extended skin contact) that grabbed his attention. View the whole series here.

The idea of releasing wines when they're mature is no longer in fashion. Late release is still enshrined into a few scant traditionalist appellations - the upper levels of Bordeaux and Rioja, for example…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Morning Claret to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.