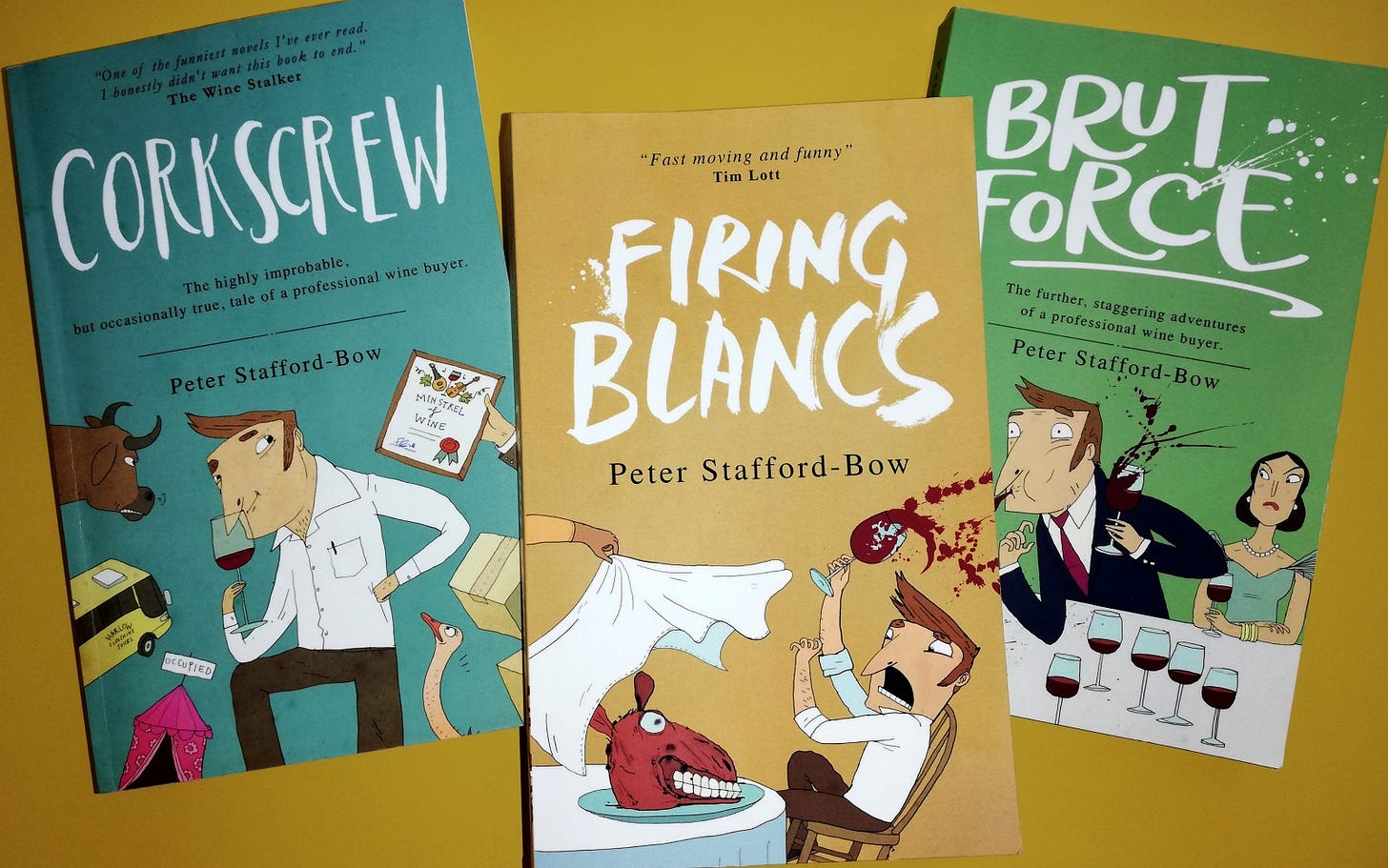

Book review: Peter Stafford-Bow - Firing Blancs

Simon reviews the new novel from Peter Stafford Bow - Firing Blancs is the third in the Felix Hart series, following on from Brut Force and Corkscrew

You might think that wine and comedy make obvious bedfellows. But certainly in the case of wine writing, this is very rarely the case. A few valiant (or foolish?) souls have tried, but the results have mostly been risible rather than side-splitting. Thank goodness for Peter Stafford-Bow, who is currently the only author I know who's really made this combination not just sing, but positively cavort naked around the room.

Let's get one point out of the way immediately. That name? It's a pseudonym - a nom de plume, if you will. Whilst I'm sworn to secrecy, I can confirm that I'm one of only a few thousand people on the planet who know this man's true identity. I've even met him in person. I would just add that even those with a bird's eye view of the industry will struggle to unmask him. No, he is not Banksy, or Robert del Naja.

Screwed

When Stafford-Bow's first novel Corkscrew appeared in 2018, I lapped it up eagerly. Outrageously baudy and ridiculously improbable, it was a huge amount of…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Morning Claret to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.