An Artist's Legacy: Marta Soares and Casal Figueira

There's a dramatic backstory to Marta Soares' life, but this artist and winemaker wants people to focus on her present not her past.

Marta Soares opens a bottle of wine to accompany our lunch at her favourite spot in the village of Vermelha - "The best taberna in Portugal!" she proclaims with a smile. The wine is Casal Figueira - António 2009, and it bears the weight of history on its shoulders. It was made by both Soares and her late husband António Augusto Carvalho, who died aged 43 in the middle of the harvest that year. Carvalho pressed the grapes, and had them fermenting in tanks at the time of his death. Soares then took over and matured the wine before its eventual bottling, with his name on the label as an homage.

I flash a look across the table at my colleague Ryan Opaz, as we both struggle to retain composure. It's an emotional moment, and not only because the wine and the plate of juicy ameijoas on the table pair to perfection. But Soares doesn't blink. She casually fills our glasses while chatting away about winemaking, art and village life.

Soares has long since moved on, and expresses slight frustration that her press hasn't always kept up. "The story has occupied a lot of space, but I've been making wine for 12 years on my own now" she says. "I'm not just this sad widow continuing the work of my dead husband. That image really doesn't suit me!"

Spend any amount of time with Soares and this becomes very clear. Art remains the major focus of her life, as shes juggles careers as an artist and lecturer on top of making wine. "I work a lot with memory and space, how they can affect you and how they find their way into both art and wine" she says.

An artist's sensibility

When we arrive at her winery in the small village of Vermelha, Soares surveys us imperiously from the loading bay, cigarette in one hand, coffee cup in the other. German minimal techno provides an apt soundtrack in the industrial space, and an abstract clay sculpture towers above her head. The huge 1940s building, an abandoned bulk winery that belonged to Carvalho's family, feels more like a hip gallery space in New York's meat packing district than it does an artisan winery in rural Portugal. Yet Soares inhabits both worlds and has made both her own.

During our visit, she opens a pair of wines that were made by Carvalho in 2006 and 2007. They represent a very different paradigm to her own oeuvre. Where her style is delicate and crystalline - "I don't want any oxidative process in my wines" - Carvalho's wines focus far more on richness and texture. Not to mention that both are made from international varieties - a dry white Roussanne and a late harvest Petit Manseng.

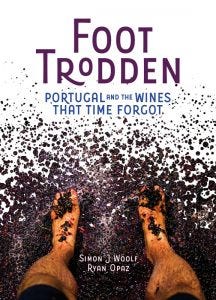

Buy our book to read more about Marta and many other Portuguese winemakers.

Admittedly, the couple had just embarked on a new project around the time of Carvalho's death. After many months scouring Portugal for interesting native grape varieties to work with, they were drawn back to Carvalho's home region. They became fascinated with the old vineyards on the slopes of the nearby Serra do Montejunto, a mountain that rises above the town of Cadaval to 666 metres. Here, wizened old Vital vines are rooted in stony limestone soils. But there isn't much love for Vital any more. Known for a rather neutral flavour profile and a lack of acidity, a significant quantity of the remaining plantings end up being distilled into brandy rather than sold as wine.

Carvalho felt that Vital grown at higher altitudes in Lisboa, with cooling Atlantic breezes never very far away, had real potential. Soares has vindicated that point over the last 12 years, showing that the variety's delicate aromas and subtle peachiness can be coaxed centre stage with sensitive winemaking. This is the only point during our three hour visit where she alludes to some emotion - "António never got to see what was possible with his vision. That still makes me cry".

Learning by doing

Soares learned her craft as a winemaker by observing and then by doing. But she has since developed her own quite obsessive methodology, and one that runs counter to many of her contemporaries in the 'low intervention' space. Soares likes to press the Vital at a glacial tempo, leaving it in a horizontal basket press for 10 hours. She'll sit patiently next to the press all night, waiting for the right moment to rack off the juice and pump it into waiting tanks. Dry ice and metal cooling rods are used to ensure that, throughout the whole process, freshness is preserved and oxidation doesn't get a foot in the door. The wine then matures in barrels, but not so you'd know.

Since 2013, Soares has also made a juicy crushed-berry filled red from another unloved local staple - Tinta Miúda, better known in Spain as Graciano. From the 2020 vintage, this wine (named simply Vermelho, Portuguese for 'red') has become a 50/50 a blend with Castelão - a variety that carries yet more emotional resonance as Carvalho was foot treading Castelão at the moment of his heart attack. Soares admits that she didn't use those grapes in 2009, and shied away from making red wine at all for several years. But Vermelho is now a regular fixture, equally as assured, elegant and delicious as the Vital.

Working the old Vital vineyards has its challenges. Soares has informal agreements with the owners of each of the five old vine plots she uses. Much of the vineyard work is done by the owners, old-timers who don't always see eye-to-eye with Soares' vision of viticulture. A disagreement about the use of herbicides in one 80 year old plot resulted in the owner churlishly ripping out three rows of vines where Soares had let the grass cover grow. Soares nonetheless has huge respect for the people she works with, especially when it comes to pruning - "the locals prune like artists" she says, "they make a new sculpture each year". Still, even if the vineyards tick many wine geek boxes (old vines, heroic viticulture on the side of a mountain), any notion of 'organic' is a distant dream.

Identity etched in chalk

Art and wine don't just combine in the vineyard, but also on the Casal Figueira labels. The small village of Pereiro, just below some of Soares' vineyards, upholds the old tradition of making chalk drawings on people's houses to celebrate Epiphany (6th January). Villagers decorate their neighbour's wall with a star of David, the new year and the initials BRM (standing for "the three wise men" in Portuguese), and sometimes a small drawing which relates to the profession or predilection of the resident - a horse, a tractor, a dog.

Soares reworks drawings from each year into the front label of "António", incorporating a little more of the wine's backstory into the package. As we drive through the village seeking out her favourite wall, there's a moment of disappointment. "They painted over the wall!" she exclaims in shock. For Soares, the chalk drawings are symbolic on many levels. "Limestone marks our aesthetic identity in Portugal, even our austerity" she adds.

Casal Figueira itself has become an abstract concept. The original estate belonged to the Carvalho family, and it was where Soares and Carvalho first met in 1999. Long since sold off to pay family debts, Soares has nevertheless retained the name as her brand. As she explains "Casal Figueira was never a place, it was a spirit. It was about not being fearful. Sooner or later you find your own way, so don't be afraid of making mistakes."

[gallery link="none" size="large" ids="13234,13238,13242"]