I Come from Nowhere (Wine Classification is an Ass)

Wine classifications guarantee provenance, but why have many of their controlling institutions become de facto style police?

This year I’m planning to visit some new wine regions. I’ve put together a killer itinerary based on what it says on the labels of my fave bottles. It kicks off in Weinland, Austria before heading to Vin (in France) and finishing up on the hip IVV coast of Portugal. Good luck finding those on the map. These deliberately non-geographic terms were hewn from the finest legalese to ensure wines that shall not speak of a place – nor be locatable in one. If that makes no sense, now read on.

In times past, the wine label functioned as a handy piece of orientation. Harvested some Sauvignon Blanc in an easterly corner of the Loire? Then you can put the name of the village – Sancerre – on the bottle. Lofty ambitions? Grand vin de Loire should do the trick. But since that age of innocence, labelling regulations have grown into real bullies. And when pre-existing wine classification laws fused with the European Union’s one-size-fits-none bureaucracy, the result was akin to reanimating Frankenstein’s monster. Wine lovers now face a strange duality. The budget booze in the supermarket flaunts a fancy regional name on the label, while the cutting edge bottle in a specialist wine shop is forbidden to give any clue as to its region, village, grape variety or even year. Such is the havoc wreaked by the seemingly innocuous acronym PDO - ‘protected denomination of origin’.

PDO is best known in its French appellation controlée guise. But the French were far from being the first to controle. Their first appellations were enshrined in 1936. Portugal, under the dictatorial Marquês de Pombal, pipped them literally at the post by 180 years. In 1756 Pombal limited port wine production to grapes grown in the Douro valley, physically marking the borders with granite bollards. Pombal nailed the PDO brief. His diktat guaranteed the provenance of port. But this clear-cut goal has since become diluted with more nebulous ideas. Most pernicious of all is typicity – a barbed term of which Portugal’s regional wine commissions now appear to be the gatekeepers. The problem? Who defines what’s typical in a wine region, and how far back does that definition go? If the supermarket plonk confected with lab yeasts, enzymes and all the technical tricky that modern wineries allow is taken as the benchmark, where does that leave winemakers working in a more handcrafted fashion?

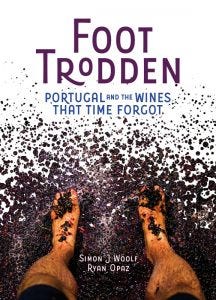

Buy our book to read more about many other Portuguese winemakers.

Antonio Madeira is a young French-born winemaker with Portuguese heritage. He makes the kind of wines that can reduce a grown man to tears. I mean that in a good way. Madeira coaxes 125-year old vineyard plots in mountainous corners of the Dão back into health, and treats them with requisite skill and delicacy in the cellar. He gave up a well-paid engineering job in Paris to move back to his ancestral region, because he found his calling making wine. Weaned on top Burgundies, he discovered that Dão had once possessed a similar reputation, before it sank into the doldrums of cooperative winemaking in the mid-20th century. The first thing he did when designing his wine labels was to put “Dão” in the biggest typeface possible, dwarfing his own name. Just for good measure, he also had corks printed up with “Dão” on them too. Then the problems started.

Madeira’s Vinhas Velhas Branco is a particularly transcendent part of his opus, a white field blend from some of his oldest parcels. It pairs Burgundian richness with a ripe, herbal complexity that is unmistakably Dão. It’s also a wine that the Commissão Vitivinicola Regional do Dão – or rather its tasting panel – seems to hate. With each successive year, Madeira has had more and more difficulty getting the wine to pass the tasting, which in turn grants the right to label and sell Vinhas Velhas as a DOC Dão wine. In some years he submitted the wine multiple times before it was accepted. Things came to a head in 2021, when the tasting panel scored his 2019 Vinhas Velhas 52 points out of 100. On the Parker scale, that’s barely even vinegar.

Sick of the humiliation, Madeira threw his remaining toys out of the pram and declassified his wine down to the lowest table wine category – the aforementioned IVV. Comparing the labels of his 2018 and 2019 Vinhas Velhas illustrates this sad tale. The 2018 celebrates its region and leaves the drinker in no doubt about its origin. The 2019 gives no clue to its whereabouts other than ‘Portugal’. All references to the Dão or the prestigious Serra da Estrela sub-region have been removed – as ordained by the EU and their proxy the CVR Dão.

Madeira’s 2019 was penalised by the tasters for oxidation. Taste the wine, and you’ll probably scratch your head as I did. Vinhas Velhas is not a homage to vin jaune or sherry. It doesn’t even channel its inner Sebastian Riffault. Be that as it may, the Commissão committed an extreme act of self-harm when they failed the 2019. Not only are Madeira’s wines a cult success, sold out on multiple continents and frequently allocated before they are bottled, he is or was one of the most vocal and proud promoters of the region. But his bottles no longer carry that message to their customers.

Madeira is not alone. Tiago Sampaio, a young winemaker based in the Douro, has had constant run-ins with its equivalent certification body, the IVDP. His main issue is that with vineyards at 700 metres above sea level, and a penchant for early harvesting and minimal intervention in the cellar, his wines are not deemed to have Douro typicité. In other words, they are not 14.5% bruisers smothered in oak. But the IVDP went one better than just denying Sampaio the chance to put the region on the label. Sampaio’s home and winery are located in the village of Sanfins do Douro. Because that name contains the hallowed PDO keyword, Sampaio was forbidden to display his full postal address on the label. Shortening it to ‘Sanfins’ was a wholly unsatisfactory solution – it’s not the name of the village. Instead, he swapped it out for ‘Alijó’ – the neighbouring town six kilometers away.

North of Lisbon, Marta Soares makes elegant, characterful wines from forgotten local grape varieties like Vital and Tinta Miúda. She doesn’t bother to try to get the wines classified as DOC Óbidos, where they’d sit shoulder to shoulder with the mediocre wine lakes produced by the coops that dominate the region, but instead declassifies to the broader and theoretically less pernickety Vinho Regional Lisboa – the equivalent of vin de pays or IGP. But in 2020 her wine didn’t even pass the VR Lisboa tasting panel. Frustrated with their unhelpful and seemingly subjective feedback that they “didn’t like the taste”, Soares resubmitted the wines with different labels. The same panel tasted and approved them. “Their job is to be objective”, she insists angrily. Her subterfuge proved they were anything but.

All over Europe, top artisanal winemakers are grappling to absolve the bureaucrats. Or they take a wrecking ball to any signs of origin on their labels. A winemaker in Bordeaux makes a line of natural wines at the same domaine where she has her day job. She admits to submitting samples of the domaine’s more classic wines in order to get the Bordeaux classification for her own line. A grower in Wagram, Austria carefully decanted sample bottles of his unfiltered Grüner Veltliner from the top of the tank, so they wouldn’t fail the prüfnummer tasting for being hazy. Further along the Danube in Kamptal, Alwin Jurtschitsch admits wearily that it took six tries to get some of his top single vineyard wines to pass the DAC Kamptal tasting panel. He resorted to double-decanting, or changing the sequence that the wines appeared in, to persuade the tasters that the delicate, mineral character of the wines was not a fault.

So why care? Wine classification is supposed to guarantee provenance and prevent sub-standard wines from being put up for sale with a prestigious name on their labels. But many of the controlling institutions have become de facto style police. Style is subjective, unlike provenance. Who’s to say that a cloudy wine made with wild yeasts is any more or less typical than a squeaky clean bentonite-fined dullard? If typicity is a proxy for tradition (another highly moveable feast), then surely the low intervention wine made the old-fashioned way ought to sail through its tasting exam.

Argue it any way you like, there is a problem when all the young guns, the hyped vignerons and the up-and-coming firebrands no longer offer any geographical information on their labels. In this new reality, wine is no longer about origin – it’s identified only by the name of its maker. What once came from a place is now just a brand. Brands are fine if you like designer clothing or easily identifiable fast-food outlets, but I prefer my wine with a little more romance.

Wine travel is supposed to be romantic too, but I guess I need to rethink the itinerary. It’s hard to visit a place with no name.

Originally published as System of a Dão in Noble Rot issue 28.