Wine on Tap - Are the Sustainability Claims just Garbage?

Can natural wine served from plastic kegs save the planet?

Search on the phrase “the wine industry’s dirty little secret”, and you might be surprised with the results. They don’t major on sexual harassment scandals, bizarre additives or health warnings. The topic is bottle weight, and the carbon footprint of shipping wine’s most popular delivery mechanism around the globe.

Mention sustainability and wine in the same sentence, and glass bottles are the achilles heel. The average 75cl bottle weighs between 400 - 700gr when empty. That’s almost the same as the weight of the liquid. Shipping so much extra mass for a product that’s often drunk just a few weeks or months after filling is hardly environmentally responsible. Worse still, the glass bottle is a lousy dispensing mechanism for restaurants or bars who serve by the glass. Leftover wine from the day the bottle is opened may or may not stay in shape for the next service. Wastage is high.

There is an increasingly popular solution. Wine on tap is serious business, especially in the UK and USA. Taking its lead from the beer industry, wine is filled in small kegs typically containing around 20 litres. These are then connected to a draft system much like that used for your favourite IPA. The kegs are kept under pressure so the wine remains fresh and free from oxygen ingress until it is drunk up.

Reusable steel kegs have used by the brewing industry for decades. But then came a disruptive innovation: the single-use plastic keg. Much lighter than a steel keg (which weighs around 10kg when empty), plastic kegs are also more convenient. Metal kegs are usually loaned to the producer or the client, and kept in constant circulation. But that means they must be shipped back to the source, cleaned and sterilised after every use. For a small winery, it can be a significant logistical challenge.

Two plastic keg brands currently dominate the wine market. They are KeyKeg, based in the Netherlands and established 2006, and Polykeg in Italy, established 2013. Both are bag-in-keg solutions that work on the same principle as bag-in-box. The keg is under pressure, so the bag collapses in on itself as it empties. The compressed air or CO2 used to pump the wine to the tap never comes into contact with the wine itself.

Both companies provide copious amounts of information about sustainability and recycling on their websites, and both talk about circularity and a circular economy. KeyKeg’s parent company even renamed itself in 2019 from Lightweight Containers to its new and slightly Eggers-esque moniker OneCircle.

The natural wine world has fallen in love with plastic kegs. Sustainability is top-of-mind for producers, importers and retailers who care about organic farming and low intervention winemaking. KeyKeg’s 20 litre keg (the most popular size) is the equivalent of almost 27 wine bottles, but with packaging that weighs barely 1kg, versus 14kg or more of the equivalent bottle weight. Massive savings on carbon emissions from shipping are not the only advantage. Wastage due to oxidation is also reduced. Restaurants and bars can serve a fresher, tastier pour to their customers, often for a lower price compared to by-the-glass from a bottle.

What’s not to like?

The problem with plastic

I got hold of an empty 24 litre PolyKeg while researching this article. When you pick up 1.3kg of plastic and think about what that looks like as waste, the importance of recycling or reuse comes into stark relief.

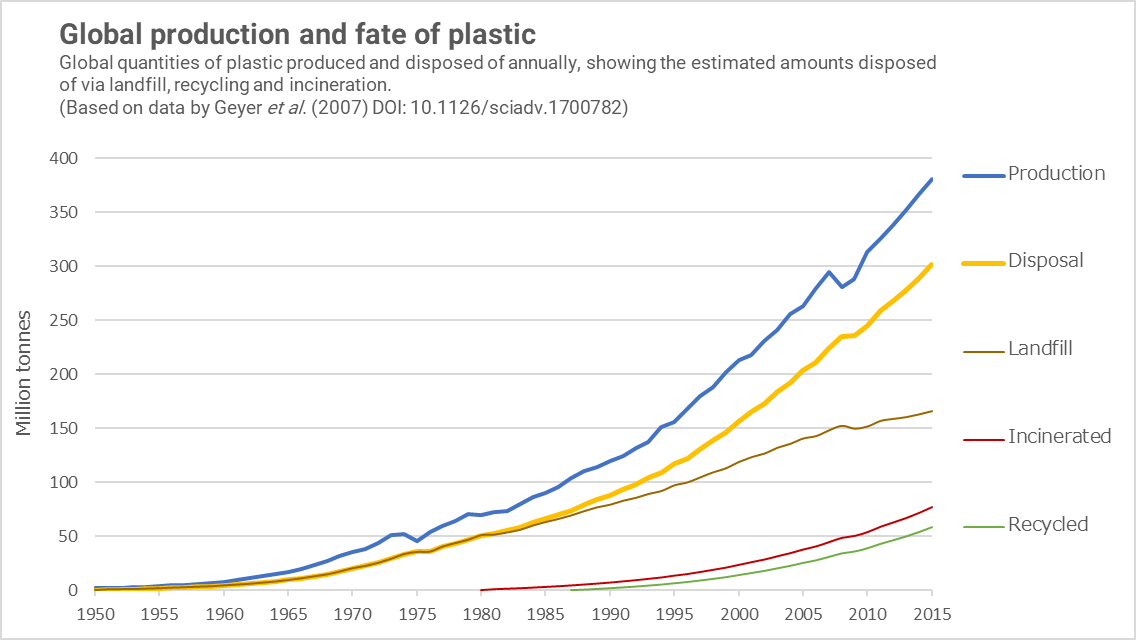

Plastic takes a century or more to break down. During that time, it leaches microplastics and chemicals into the soil, waterways and ultimately into our bodies. Compare this to glass, which can take a million years to degrade, but doesn’t carry the same toxic payload while doing so. Some types of plastic are recyclable. But ‘recyclable’ does not mean they will actually be recycled. There are huge challenges with the collection and sorting of plastic waste, and recycling plastic is expensive. Furthermore, plastic downgrades rapidly as a consequence of recycling, unlike glass which can be recycled almost infinitely. Much recycled plastic is only suitable for low-grade products such as traffic cones, where the cycle ends.

A Greenpeace study from 2022 estimated that even with PET, the easiest type of plastic to recycle, no more than 20% is actually recycled. The rest goes into landfill. The plastics industry and its lobbies work hard to convince us that plastic recycling works. But the reality is very different, as this video makes clear.

Consider this symbol, which probably makes you feel good when it appears on packaging:

It’s the universal recycling symbol, created in 1970. Most plastic packaging contains a very similar looking design, which looks something like this:

But that’s not the recycling symbol. It’s called the Resin Identification Code, and it’s effectively a cleverly designed scam to make people think that plastic is much more sustainable than it really is.

Can plastic kegs be sustainable?

Set against this backdrop, it’s hard to understand how single-use plastic kegs like KeyKeg or PolyKeg could ever claim to be sustainable, especially compared to reusable steel kegs. I put this to Kilian van Woerkom from KeyKeg, who previously worked on the production side of the company but is now account manager for the Benelux and South Africa.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Morning Claret to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.