Valentina Passalacqua - an inconvenient truth?

The arrest of Valentina Passalacqua's father, on charges of using illegal labour gangs (caporalato) has shocked the natural wine world - who were previously in love with Valentina and her wines. Simon J Woolf investigates and sets out the background and t

Valentina Passalacqua is a name that's made headlines all over the wine press in the last few weeks, for all the wrong reasons.

Passalacqua is a biodynamic winemaker based in the province of Foggia, Puglia, who markets her wines under the brands "Valentina", "9 is enough" and "Calcarius". She was the darling of the natural wine world - and particularly of importers and distributors who appreciated her well priced wines, until just a few weeks ago. Then on July 1st her multi-millionaire father was arrested in connection with his vegetable business (Tenute Passalacqua srl) and accused of caporalato - the practice of recruiting and coercing migrant labourers by caporale (gangmasters) to work for appallingly low wages, and to live and work in inhumane and often dangerous conditions.

Passalacqua quickly tried to distance herself from her father's empire, and initially garnered respect from the natural wine community for doing so. However, as more damning accusations and facts emerged, much of that support has ebbed away. The reporting from Glou Glou Magazine and Left Unread has been particularly strident, causing many distributors to de-list her wines and a whole army of keyboard warriors to turn on her. Questionable labour practice is in no way compatible with the perceived ethics of the natural wine world.

Meanwhile, Passalacqua continues to assert her innocence.

Could she be oblivious to her father's activities? Is she a naive rich kid, or just an honest woman trying to develop an ethical wine business outside the constraints of her father's influence? And did she really come from nowhere to overnight success in natural wine, as the entire American press seems to believe?

Mensis horribilis

There has been plenty of reporting, but it has tended to be more emotive and less detail focused. Eric Asimov's piece in the New York Times provides a solid summary, and a reflection on what this means for the industry. Not surprisingly, Passalacqua herself has become increasingly tight-lipped, and as reported by Asimov, has engaged a crisis PR firm to help with communications.

Passalacqua's public silence is understandable, given that nothing is decisive until the outcome of her father's court case. No date for the trial has been announced. Two further developments have added to Valentina's plight. On August 5th, she posted on Instagram that her mother had passed away. This was confirmed in a private message to The Morning Claret. Then during the evening of August 11th, her father Settimio was admitted to the local hospital's emergency ward (Pronto Soccorso). Valentina was by his side.

Pending an expected interview with Valentina, this piece sets out relevant details and context for those interested in the affair. It is based on a visit to the estate in 2017, numerous meetings with Valentina at tastings in 2018 and 2019, an interview conducted with her in April 2020 and additional sources contacted over the last three weeks.

The facts so far

Valentina's father Settimio Passalacqua (78 years of age) was placed under house arrest by the Carabinieri on July 1st. Also placed under arrest was Settimio's right hand man Antonio Piancone. Here's a video from a local TV station which shows the carabinieri investigating working conditions at the Tenute Passalacqua estate.

The specific complaints as detailed by the judge are that Settimio and Piancone "used, hired and/or employed manpower consisting of a very significant number of EU or non-EU workers of various ethnic groups - mostly African ethnicity and Albanian ethnicity- taking advantage of their state of need, attributable to precarious economic conditions, and severally, to the shortage of alternative employment opportunities in the locality of residence, the lack of assets and alternative sources of income, the level of schooling and the condition of immigrant for some of the workers employed and ultimately the circumstance that the aforementioned had arrived in Italy in search of safety and a job that could guarantee their survival and that of their family members."

The exploitation consisted of "the repeated payment to workers, mostly by means of cash, of the hourly sum varying between a minimum of € 3.33 and a maximum of € 5.71 or a daily wage between 30 and 45 euro, in violation of national or territorial collective agreements stipulated by trade unions ". Furthermore the labourers had to work seven days a week, with a theoretical 30 minute lunchbreak often denied. Holidays and sick leave (even absence due to sickness) were not granted either.

There are also fraud charges that Settimio's various companies engaged in a scheme where fictitious employment contracts (for workers who either didn't exist or didn't show up to work) were used in order to claim government relief which totalled some 650,000 Euros during the first half of 2019 alone.

More about caporalato

The judge does not detail some of the other practices that are common under caporalato - workers are typically accommodated in basic conditions which may or may not have luxuries such as running water or proper toilet facilities. Payment for this accommodation is subtracted from wages, along with other deductions for transportation to and from the fields or the provision of drinking water. Passports, where workers have them, are usually confiscated during the period of employment. The worker is then effectively trapped without legal recourse, should their already meagre payment not be forthcoming.

Caporalato is still common in the huge agricultural area around Foggia, despite continued attempts to regulate against it. It has been dubbed "modern slavery", and implied links with the mafia are never far away. For excellent reporting into this ongoing blight on Southern Italy's vegetable industry, see these long reads in Time magazine, The Guardian and L'espresso.

In good company?

Various Passalacqua family businesses could be implicated in the arrests, via the involvement of Settimio Passalacqua. They include Tenute Passalacqua srl società agricola, Passalacqua Settimio, Passalacqua Nazario Guido and Passalacqua Pierpaolo. Valentina Passalacqua has asserted that her business is not linked to her father's in any way. A look at the Italian chamber of commerce records confirms Valentina's statement that her company is owned solely by her.

One interesting detail that has been little reported outside of Italy is that Tenute Passalacqua srl has organic certification. Settimio has previously been in trouble for not obeying organic standards, according to FederBio (the Italian federation of organic and biodynamic farmers).

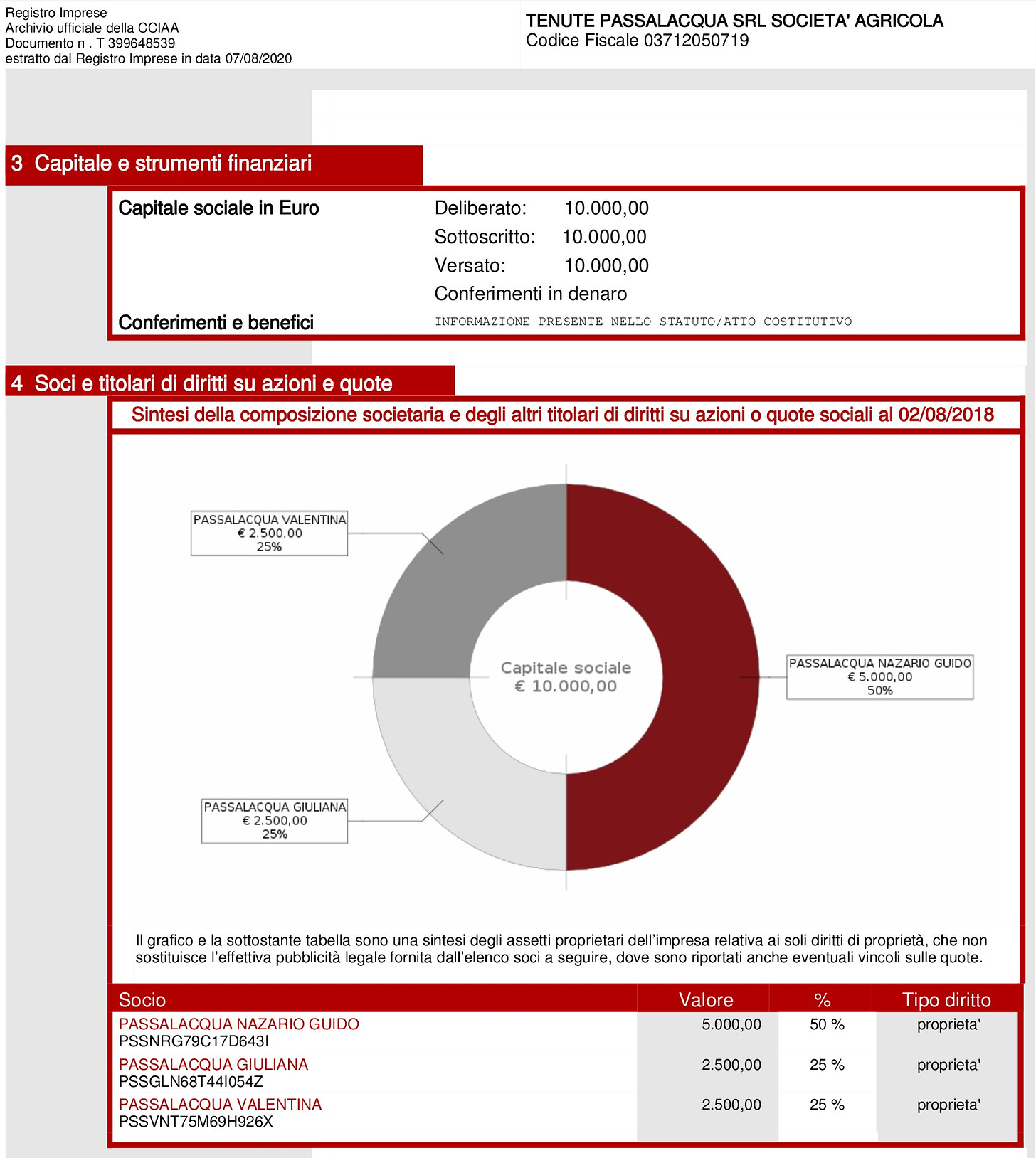

Valentina has repeatedly asserted that she was not aware of her father's employment practices, and that her company and her father's are completely separate. However, one of the family companies, Tenute Passalacqua srl società agricola, has her listed as one of its three partners (together with two other family members). As can be seen from this excerpt from the Italian chamber of commerce records, Valentina has a 25% share in the company. Thanks to Glou Glou magazine who unearthed this detail.

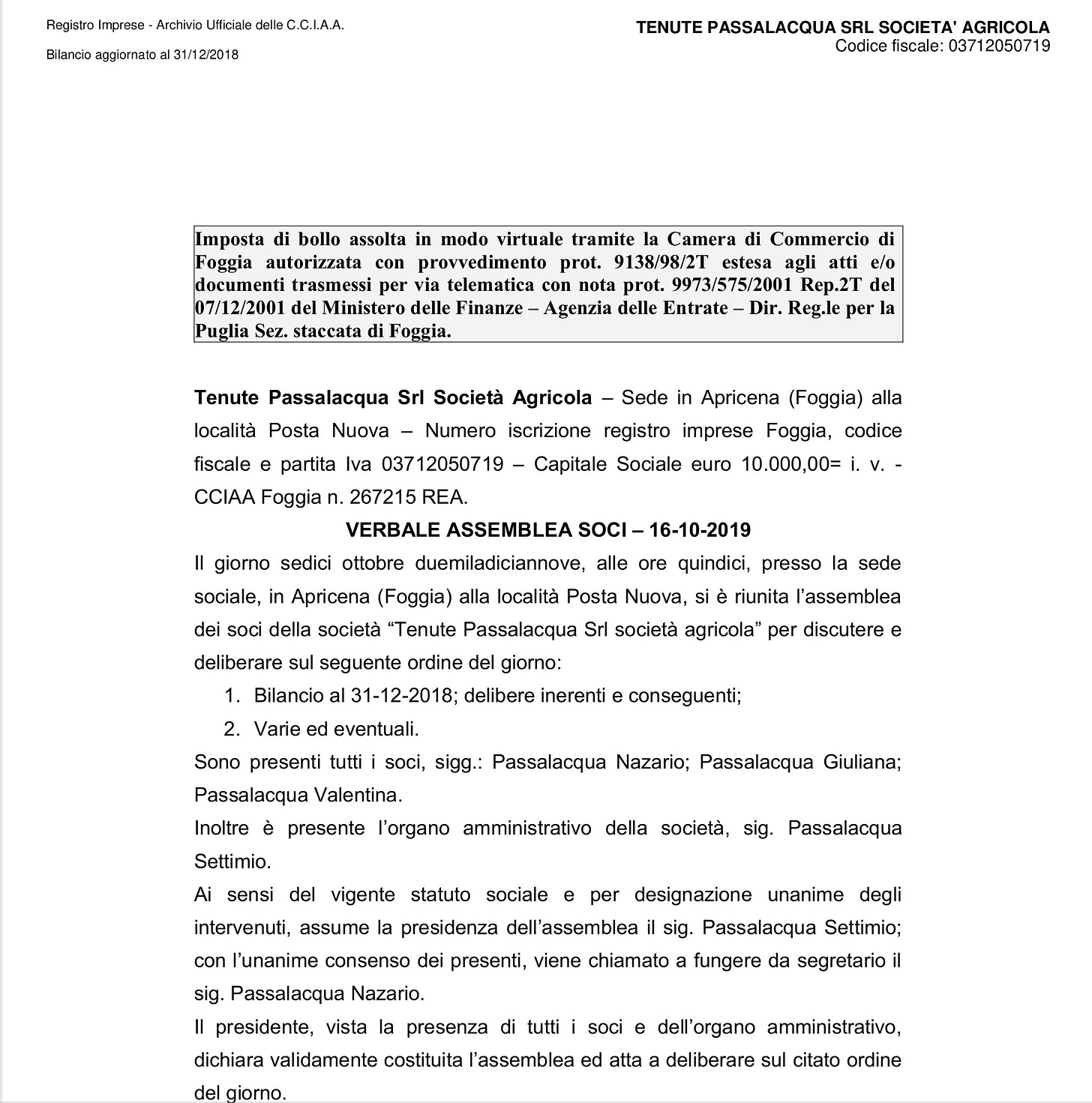

It should also be noted that Settimio is listed as the administrator ("il presidente") of this company. Whilst it would be theoretically possible for Valentina to be a sleeping partner, records lodged at the chamber of commerce show that she attended a shareholders meeting of the company on 16 October 2019. Also present were Nazario Guido, Giuliana and Settimio Passalacqua.

A source in Puglia who did not wish to be identified told The Morning Claret "The company is managed by the father even if the children are in charge of activities. But the person who commands, decides and pays is the father. In that company nothing is done that is not decided by the father. Valentina, however, is her father's favourite daughter and therefore has a strong influence on him."

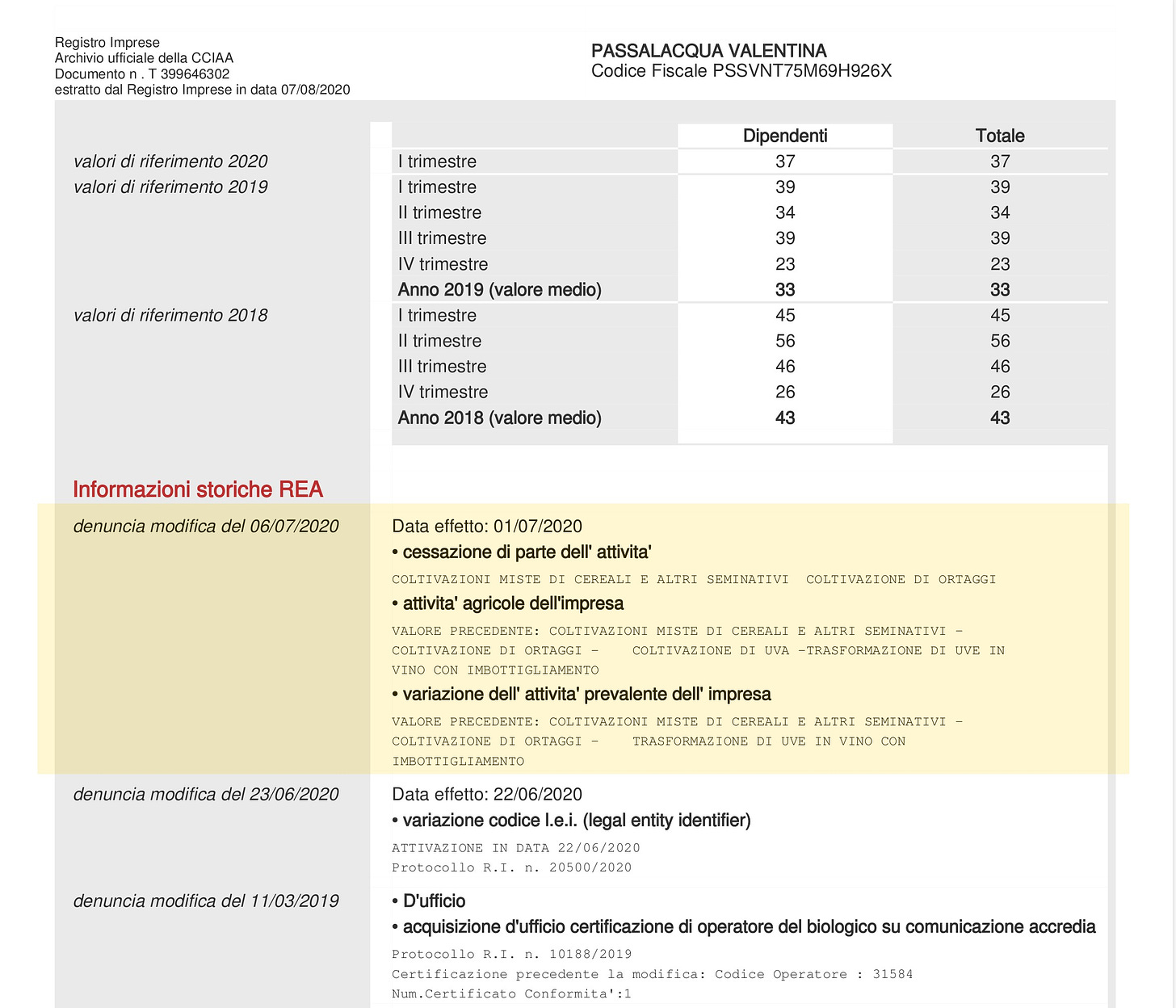

Valentina amended her personal company details on July 6th 2020, five days after her father was arrested. The amendment can be seen below (shaded yellow), in the historic "visura" of the company document filed at the chamber of commerce. The amendment has an effective date of July 1st, and changes her company's primary business activity from vegetable and cereal growing to the production of wine. Furthermore, the vegetable and cereal growing side of the business is noted as ceased on the same date. This looks like a panicked attempt to create as much separation as possible between her father's business and her own. Glou glou magazine asked the rhetorical question "is that what an innocent woman does?"

Whilst this kind of amendment could be seen as just keeping the record neat and tidy, the timing is poor to say the least. Then again, Valentina has a law degree, so it shouldn't come as a surprise that she tried to get her house in order. Was this an advisable move? Perhaps not, but on its own it certainly does not prove or disprove that Valentina was complicit in her father's alleged crimes.

Valentina's background

Valentina's original career was in law, but she decided on a complete life change just after the birth of her first daughter (she now has two) in 2008. She moved from city to countryside (she now lives just a few minutes away from her winery, in an isolated location in the Gargano national park area), and changed her focus to farming.

Valentina's own company (the Valentina Passalacqua sole proprietorship) was formed not in 2008 but in 2006, with its core business listed as "Mixed crops of cereals and other seeds, cultivation of vegetables". The transformation of grapes into bottled wine was listed as a secondary activity. It is worth noting that Tenute Passalacqua srl and Valentina's company are based very close together in the municipality of Apricena.

From 2010, Valentina started her wine business in earnest, utilising 45 hectares of vines which had been planted in 2000 (and which were presumably owned by Tenute Passalacqua srl or one of the family's other companies). Indulging her stated passion for architecture, she built an impressive modern winery. Hardcore natural wine fans may be surprised at its scale. The complex is extremely grand, with luxurious furnishings, sculptures and decor. It's hard to estimate the cost of construction, but estimates around 20 million euros would probably be conservative. It's more redolent of a James Bond film set than the rustic cantina of a natural wine grower. It's also full of marble, which was the Passalacqua family's route to fortune. Settimio still owns a huge marble quarry in the region.

The winery

During The Morning Claret's visit in October 2017, we saw the new barrel hall, where Valentina has created a structure that she describes as "womb-like". It occupies the lower levels underneath an equally grand reception area, which could easily hold several hundred guests. I met Valentina's 10-strong core team, all young and bright-eyed. They had the air of a gang of enthusiastic interns. We ate dinner communally at the winery - apparently (and to the clear appreciation of the employees) a nightly fixture.

We were not shown inside the vast building which houses the main winery. This building sits behind the public complex which houses the reception, guest accommodation and barrel hall. It has an equally imposing frontage which shelters a huge industrial looking rear. The space looks like it could house a winery making millions of litres of wine a year.

I took a walk in the surrounding area as the sun was going down. It's isolated and very rural, and not hard to see how the practice of caporalato persists in this province. A few hundred-strong teams of illegal workers would be quite invisible here - this is not to suggest that Valentina Passalacqua uses such teams. The winery visit was interesting, if a little uncomfortable. Valentina didn't seem to be at ease.

I was put up in luxury in one of a whole corridor of guest rooms above the winery reception. The next morning, we were invited to Valentina's nearby house for breakfast. It was another uneasy occasion. Breakfast didn't materialise, and even coffee capsules for the coffee machine couldn't be located. I did get a chance to admire the infinity pool in Valentina's garden.

Jenny Lefcourt (co-founder of the hugely influential New York-based natural wine importer Jenny & Francois Selections) says in an Instagram post from July 24th that "She [Valentina] created her winery with her own money, as well as a grant from the Italian government for women entrepreneurs under 40 looking to create businesses in regions of economic devastation." It's hard to imagine that any such grant would come close to covering the costs of Valentina's winery.

Lefcourt initially came out in support of Valentina, before having to backtrack in the face of the damning insights published by Glou Glou magazine. Jenny & Francois' current position is stated in a further Instagram post dated 31st July: "As of today, we are no longer representing the Calcarius brand."

Not so sudden

Valentina started to market her wines from 2011, and there are many publicly available video clips and interviews which show her at VinItaly and other events over the years. Her branding seems to have taken a while to nail down. This clip from 2011 shows her stand at VinItaly, with the tag line "eco minded". By 2017 she'd settled on a modern if bland labelling scheme. The brand name was "Valentina Passalacqua", and the wines were either just named after their grape varieties (Nero di Troia, Bombino and Primitivo, for example) or with lighthearted monikers such as "Cosìcomè" or "Litos". At this stage, her international profile was still close to zero, and she lacked distribution in many markets.

The wines were good but not great, and in some cases a bit raw. The impressive botti grande shown in the photos of the barrel cellar were not yet in use, and everything was being aged in stainless steel tanks.

Valentina's big breakthrough came with the 2018 vintage. She created a new product line called "Progetto Calcarius", avowedly to show wines made from the more calcarius (clay/lime) soils on the estate. It was tailor-made for the thirsty natural wine market: all the wines are bottled in clear glass, many in one litre bottles, with bold and funky labelling that imitates the periodic table. The wines are light, low in alcohol and easy-going - Puglian glou-glou, in other words.

The natural wine market has had a feeding frenzy with these wines, in large part due to their relatively low pricing and ready availability. Although Valentina told me that the estate had 45 hectares of vines in 2017, the more recently reported figure is 80 hectares. This would represent a major amount of new vine planting in just three years. It could also be due to the acquisition of other vineyards, however during my walk around the area, I did not see a single other vine outside the Passalacqua estate.

Sources in Puglia have suggested that Valentina's numerous branding and strategy changes with respect to the wines are bound up with her father's refusal to back some of the concepts. From afar, it looks more like a struggling business that didn't get its marketing right for the first seven years. Sales and return on investment must have been slim during this period.

When US journalists talk about Valentina's sudden rise to popularity, they're really only talking about Progetto Calcarius. In all other respects, Valentina has taken a long and slow path to success, becoming enthused with biodynamics along the way. She has certainly put in the hours when it comes to promotion. I happened across Valentina personally on the stand at numerous wine fairs during the period 2018 - 2019 - Renaissance des Appellations in Vienna, Raw Fair London, Salon St. Jean in Angers amongst them.

Valentina herself also had a remake roughly around the time of the launch of Progetto Calcarius. When I first met her in 2017, she looked more like a lawyer than a natural wine grower, dressed and coifed smartly and conservatively. Her image didn't suit the brand - if she wanted to play with the cool kids at natural wine fairs, something had to change. In February 2019, I met Valentina at Salon St. Jean, in Angers. This is a large tasting organised by Renaissance des Appellations, which takes place just a day or two before the infamous La Dive Bouteille. She was unrecognisable (I walked right past her stand) - she'd had a complete make-over, and now sported punky pink-blue hair, a T-shirt and jeans. She also seemed much more relaxed.

Valentina isn't the first natural winemaker to carefully curate her image and she won't be the last. Natural wines need a story and an image to help them sell, just like anything else.

Industry reaction

Salvos have been fired at businesses such as Jenny & Francois Selections, with pundits accusing them of not doing due diligence on Valentina before they signed her up. In fairness, importers and distributors have sales as their main priority, and natural wine does not come with a built-in fair-trade mark (even if that is implied). If importers investigated the labour practices of each of their producers in detail, many more murky cases would come to light. No-one showers their harvest workers in gold, and these seasonal jobs are invariably filled by the cheapest immigrant workforce available.

Whilst two notable US importers (Zev Rovine Selections and the aforementioned Jenny & Francois Selections) have publicly stated that they have dropped Valentina from their portfolios, many others have opted to sit on the fence. The Morning Claret contacted Valentina's distributors and importers in many other countries. Most were not willing to go on record, or have communicated only via prepared statements on their websites. Many are waiting to see what the court case or other insights bring.

Raw Wine, the hugely popular series of natural wine fairs that took place around the globe (and hopefully will take place again in our Covid-aware future), removed Valentina's listing from their site, and their founder Isabelle Legeron commented "We have disabled her profiles on rawwine.com for the time-being, while we look into it all but it is too early to say whether or not Valentina will be able to exhibit at future fairs yet as we need to establish the facts first. The well-being of communities is fundamental to what we do (in fact it is even part of our brand symbols) and we expect it to be at the core of our grower’s beliefs as well."

Valentina's UK distributor, Les Caves de Pyrene, has decided to give her the benefit of the doubt. Les Caves' MD Amy Morgan told Drinks Business "We feel it would be both unethical and unfair of us to condemn Valentina for the alleged actions of her father. We have spoken at length with Valentina herself and are assured that she was not aware of any such exploitation, has had no part to play in the activities that her father has been accused of, and is devastated by the allegations."

A lot is at stake here, and the natural wine industry is hurting. It has also closed ranks. No-one wants to be taken for a ride or find themselves with an ethical disaster on their books, but no-one wants to lose the cash cow that is one of the most visible natural wine brands of the last two years. Not to mention that many distributors are sitting on unsold stock of Valentina's wines, representing sizable investments that need to be recouped.

So what's the issue?

There are two key questions that everyone wants answered: Does Valentina Passalacqua make use of illegal labour gangs in her winery business? And was she aware of her father's business practices and of the alleged caporalato?

I asked another wine grower in Puglia for comment. Australian Lisa Gilbee now makes wine in Manduria together with her husband. Their winery, Morella, specialises in Primitivo. Gilbee couldn't comment on Valentina Passalacqua's labour practices (or those of her dad), however she says "the situation of caporalato has been associated mainly with harvesting tomatoes", adding that the price wars caused by supermarkets are what has exacerbated this situation.

She explains that "the wine grape industry historically has had its own workforce with various levels of experience and specialisation. There is a long tradition of agriculture and there has usually been a good local work force". She also notes that increased mechanisation in Puglia's vineyards has balanced a corresponding reduction in the local workforce. In contrast, she says "we have read about this problem in vineyards in Piedmonte and other northern regions." - presumably as there is far less mechanisation there due to steep and hilly vineyard sites.

By implication, it is far less likely that caporalato would be used for grape harvesting, and indeed Valentina has steadfastly denied this as well. That said, 80 hectares is a very significant vineyard surface to harvest. Depending on vine density and seasonal weather, a team of 100 grape pickers might need to work for three or more weeks to bring everything in. Valentina's business had 37 employees as of spring 2020, and many of these would be administrative or office workers, not vineyard labourers.

It is also possible that Valentina machine harvests some of her vineyards - this would make sense especially for the Calcarius line. There is nothing in either organic or biodynamic certification schemes that would prohibit this, even if the idea would outrage natural wine aficionados. It would however put her at odds with Renaissance des Appellations, whose charter forbids machine harvesting. That said, it looks as though her membership of that organisation has lapsed.

The second question is more troublesome. Given all the evidence and Valentina's family ties, it is very hard to believe that she could not have known about her father's alleged labour practices. Commentators in Puglia, and experts on the region all suggest that she was either turning a blind eye, or must have been incredibly naive.

What should Valentina do now?

Irrespective of the outcome of her father's case, Valentina has lost the trust of a very large part of the natural wine industry. To regain it will require a huge effort. She will need to explain how a 25% share in Tenute Passalacqua srl is compatible with her initial denial of any connection with her father's business, and why she rushed to change her company record at the chamber of commerce on July 6th.

She will need to be more than transparent, to show that any seasonal workforce employed for this year's harvest are being properly paid.

Valentina's latest line of wines are named "peace". They comprise four pet nats, "Peace Pet Bianco", "Peace Pet Orange", "Peace Pet Rosé" and "Brutal Peace". The website's tagline is "Peaceful living".

Her personal belief in sustainable agriculture, organics, biodynamics, natural wine and peaceful living seems heartfelt and has been consistently stated over many years. Now, though, actions rather than words are needed.

--------------------------

Disclaimer: Valentina Passalacqua provided complimentary accommodation and dinner when I stayed at the winery for one night in October 2017. The purpose of my visit was research for an article on Puglia and its wines, for Decanter magazine. As Decanter does not cover any expenses, it is standard practice that journalists usually seek to cover as many travel, board and lodging costs as possible. I visited many other wineries during the trip, where I also received hospitality.

In the article, which was published in Decanter's Italy supplement in January 2018, I did not profile Valentina Passalacqua, however I did review and recommend one of her wines, which received a score of 90 points.

--------------------------

Correction: two weeks after this article was published, I interviewed Valentina Passalacqua together with her lawyer Giacomo Woodhead Angemi. Some details about Tenute Passalacqua were clarified, and these have been amended in this article. The original version of this article wrongly stated that Tenute Passalacqua SRL was the company at the centre of the allegations and Settimio Passalacqua's farming operation.