How Challenging is it to Make Natural Wine in China?

An interview with winemaker Ian Dai

I got to know China’s fast-developing natural wine scene in 2023, via two separate visits to Shanghai. Most exciting was the discovery that there is a growing group of natural winemakers getting to grips with the potential of the country’s extreme climates. If one winemaker stood out, it was Hongjing Dai, better known to westerners as Ian Dai. His elegant and often delicate wines made from different Chinese regions surprised and delighted me. Unlike the first wave of Chinese winemaking in the early 2000s, which seemed only about imitating French classic wines, what Ian is doing feels quite distinct from anything European.

We caught up in Shanghai again this November, and enjoyed a two hour conversation about Ian’s career and the Chinese wine scene in general. He’s not only a skilled winemaker, but also an erudite and philosophical thinker.

I hope readers will find the discovery of a nascent wine industry with its own unique challenges as fascinating as I do. Paying subscribers can also enjoy a 30 minute audio excerpt from our interview here.

When I ask how he got into wine, Ian Dai breaks out into his infectious giggle. “it was such a random thing” he says. After attending high school in Australia – hence the stellar command of English - he had an argument with his parents and dropped out of education altogether. After two lost years in Shanghai – “I don’t remember what I did but I basically did nothing” - he decided on a complete change. “I wanted to be a barista or a sommelier” he says. “And then I found this job in a wine shop.”

Ian didn’t enjoy it in the beginning because he only got to taste “cheap stuff”. Things improved slightly when he moved into the sommelier world and a job for a big hotel chain. “I could go to all these tastings and I started to slowly appreciate wine. But being a somm in Shanghai was a boring job.” This was 2013, long before the city’s wine scene exploded into its current smorgasbord. “My main job was just to make sure we had enough inventory in each outlet” he says.

By 2015, Ian had enough of somming, and changed to what he describes as “wine consultancy” - organising wine events, competitions and teaching. He was invited to teach in Ningxia (China’s most famous wine region), which was booming at the time. It sparked a lightbulb moment. “Outside the classroom was a vineyard” he recalls, “and I remember thinking I’m not that far away from winemaking.” But he adds “back then most of the wine tasted so bad. It was industrial recipe wine. People just didn’t care. And I thought if I make something, it has to be different.”

Finding the Fruit

He mined his contacts to try to find a source for grapes or vineyard land to rent, initially without success. It took two years before he found the right partners and a friend who came on board with a modest amount of investment. He admits that “if I realised it was going to be that difficult, I would never have done it. But there was no turning back.”

Ian eventually succeeded in finding professional growers to work with, and made his first vintage in 2017. His brand Xiao Pu, translating as “small garden” was created the same year. He knew he wanted to do the exact opposite of what all the big Ningxia wineries were doing at the time – making very technical wines on a large scale, with yeast and enzyme additions and every possible intervention.

His hunch came not from experience but just from reading about how fine wines were made in classic French regions such as Chateauneuf-du-Pape or Burgundy – “all the things I read about Pinot Noir, the Rhone valley and so on were mentioning wild fermentation, so I said OK let’s just do it.” Dai didn’t have any training as a winemaker per se, although he completed his WSET Diploma and entered the Master of Wine programme. He never finished it. “You have to spend so much time studying conventional wine and the commercial side of the industry. I just hated it” he explains.

Dai got lucky with his fledging 2017 wine. “We tried one batch [with wild fermentation] and it tasted delicious – nothing went wrong!” The following year was more of a rough ride and Dai learnt that natural winemaking doesn’t always go according to plan. From 2018, he started working vintages in the southern hemisphere to gain more experience.

Time spent in Australia working for Bleasdale (Langhorne Creek), Pierro and L.A.S.Vino (Margaret River) brought vital learning. “At Bleasdale they were fermenting Shiraz in an open concrete tank. Or you could call it a swimming pool!” says Ian, adding “in China no-one does this, everyone uses closed vats.” It inspired him to try wilder, less controlled fermentations in his own wines. In South Africa, he worked vintage at Momento winery, where the team were delighted with their acquisition of a very basic old screw press. “A lesson I learned was to scale down. Work with whatever you have.”

He namechecks a number of European winemakers who have been influential. Tasting with Martin Arndorfer (Kamptal, Austria) in Vienna, he was fascinated with the idea of skin fermenting with the skins of one grape variety and the juice of another. The wines of Mythopia (Valais, Switzerland) and Radikon taught him that volatile acidity could be a valid and delicious component, adding excitement to the wine’s nose.

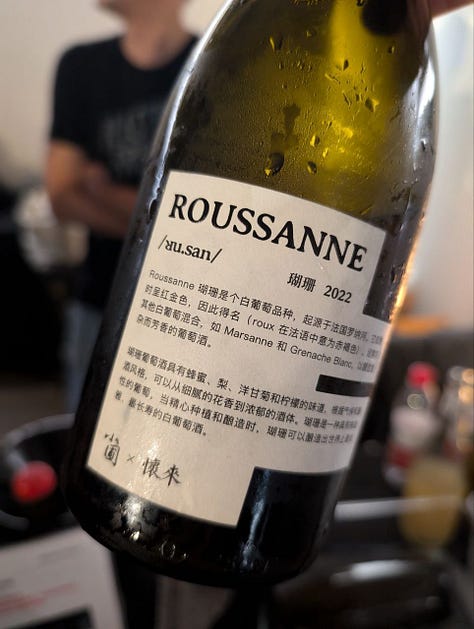

I was curious how Ian came to natural wine. Perhaps typically of his generation in Asia, he embraced it instinctively. “2017 is the year I started to make wine. And that’s the year that natural wine became a thing in Asia – apart from Japan where it existed since the 1990s” he says. “Everyone was drinking natural wine and nothing else, just because it was different”. He readily embraced the unfamiliar flavours and styles and also got the orange wine bug. Now he skin ferments most of his white blends, albeit often for only a few days before pressing off the juice.

Flying Winemaker

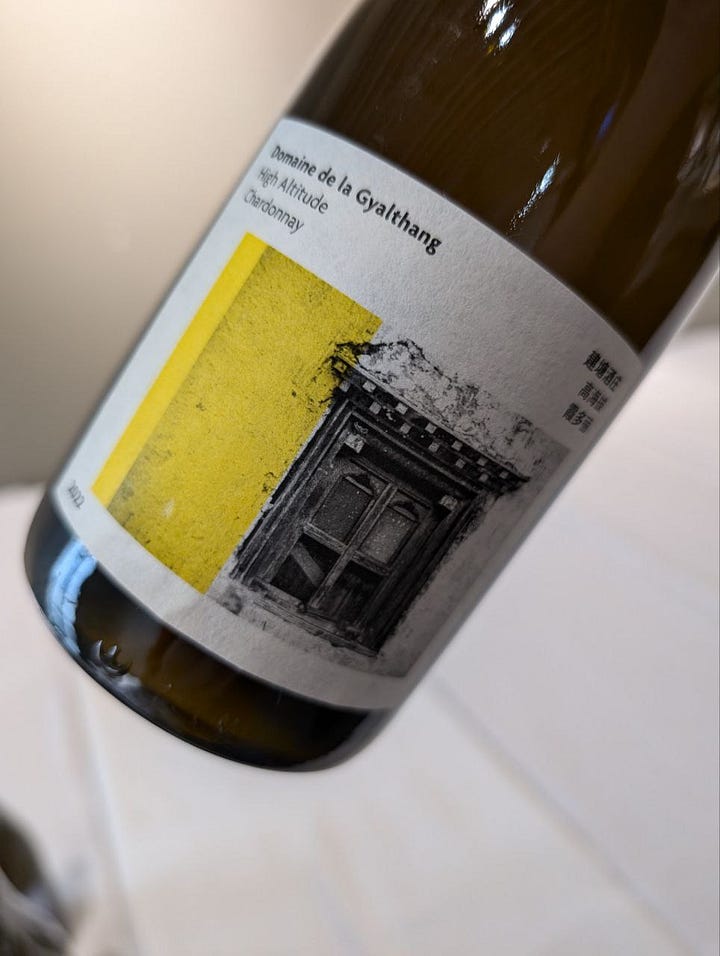

Ian now makes a bewildering number of different cuvées from six different wine regions across China. It requires a huge amount of travel, as he tries to be present in each vineyard location at key moments such as pruning – and of course harvest. Some of my favourite wines are the “high altitude” line he produces in the region now called Shangri-La1 – a mountainous area just east of Tibet, with vines growing at around 3,000m a.s.l. or more. Ian hates the name, describing it as “cultural appropriation”, and labels his Shangri-La wines “Domaine de la Gyalthang” – a reference to the original Tibetan name for the region.

He’s still figuring out how to acquire land or at least to be able to manage his own vineyards. Land ownership is a concept that doesn’t really exist in China, as all real estate ultimately belongs to the government. Vineyard land can only be rented for a maximum period of 40 years. In the more remote regions where vineyards can be planted or already exist, the local villagers have all the rental contracts tied up and are often resistant to outsiders who want to sub-lease or work the land.

I asked Ian about the challenges with viticultural practice. He admits that “it’s very difficult in China.” Whilst there are a couple of organic certified estates in China, this is the exception not the norm. That said, Ian explained that “most of the regions in China are too dry, and they don’t have problems with mildew. So they don’t spray fungicide.” Irrigation is another matter, and Ian’s opinion is that it’s more or less impossible to get a harvest without additional water. He points out that regions like Ningxia were basically desert before the vineyards were planted. He’s optimistic that a plot he now manages in Yunnan might work with just two short periods of irrigation per year, after winter pruning and before spring pruning.

Consistency

You might imagine that such an itinerant winemaker who works with rented plots and ad hoc corners in different wineries around China would struggle to achieve a consistent style. But Ian’s wines have a recognisable signature. Almost always on the lighter side, with carefully judged harvest dates, they are elegant and restrained, light on oak influence and focused on the fruit character. Perhaps not surprisingly, this reflects Ian’s personal drinking preferences. Talking about more mainstream styles, he says “Take a [classic] Cabernet Sauvignon, perfectly integrated oak, extraction, everything. I can drink a glass. But that’s it.” His preference is for fresher, less finessed wines.

Although he spent the first couple of vintages pushing the envelope, trying very long skin contact with some of the whites and even making a late harvest Petit Manseng in 2018 (it reached 16% alcohol naturally), Ian’s style and working ethic have gradually crystallised. “I’m trying to have balanced wine, always wild fermentations, and working with local villagers to put something back into the local community” he says. “I just work with what I have to make a delicious wine.”

Currently, Ian’s biggest market is mainland China, but he also sells in Hong Kong, Macau, Thailand and Australia. Japan is on the radar, but only when he finds the right partner. His view on pricing is that the wines should be affordable and accessible to everyone: “For me wines are to drink and to share with people. It should not be something you just put in the cellar.”

It’s a view that speaks volumes about both the man and his wines - quietly ambitious but never less than convivial, humble and joyful.

If you want to try Xiao Pu wines, your best bet is to head to Shanghai or one of China’s other major cities with an established natural wine scene - these include Shenzen, Chengdu and Beijing.

In Shanghai, you can enjoy Ian’s wines at countless wine bars and restaurants including Blaz, Barbar, Merchants and Where Peaches Grow.

The wines are not currently available in Europe.

The Chinese government chose to rename the region in 2001, adopting the fictional name Shangri-La from James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon.

How do you feel about making natural wines in regions where it's impossible to grow vines without irrigation? Seems contradictive.. curious what you think of it!

As it is to make it in Bulgaria...